Kanban Evergreen: The size of the ticket

Every Kanban trainer has their own set of favorite questions that seem to come back over and over again during each and every class.

Here is my personal list:

- Can we move items backward on the Kanban board?

- How do you establish your first ever work-in-progress limits?

- What should be the size of the ticket in the Kanban system?

- Should we include waiting items (items in “parking lot”) in work-in-progress limits?

If you have ever asked yourself any of these questions, here I come with the answers!

We will start from the question:

What should be the size of the ticket in the Kanban system?

Tickets on a kanban board should represent work items that are meaningful to the customer, i.e. they reflect the request made. If I order a pizza, the ticket on the customer-facing board should represent a request for a pìzza. If internal to the restaurant, the chef asks a cook to chop onion, then the service being provided is chopped onion and the ticket should represent this request.

Tickets should always represent the request being made of the service provider.

The size of a ticket is irrelevant. What is the “size” anyway? Is it the number of hours spent? Or maybe story points assigned by developers?

Tickets go on the board and they flow. Although it may sound counterintuitive, Kanban doesn’t really care for the size of items. Understanding which work item types you have in your service is a more natural way to cluster them than estimating the size of work.

As a general rule, you want to see the ticket flow. If a ticket doesn’t move on your board for a few days or longer, and yet work is being done, then perhaps you need to consider a two-tiered board with smaller, finer-grained requests that spawn from the coarse-grained customer request. The key is to see the flow and to have tickets that represent meaningful pieces of work deliverable to the requester.

So, how to deal with estimation?

Don’t estimate!

This guidance has been true since the very first Kanban case study at Microsoft XIT in 2004. Do you remember how much time they wasted on delivering estimations which have never been kept instead of focusing on their real, value adding work?

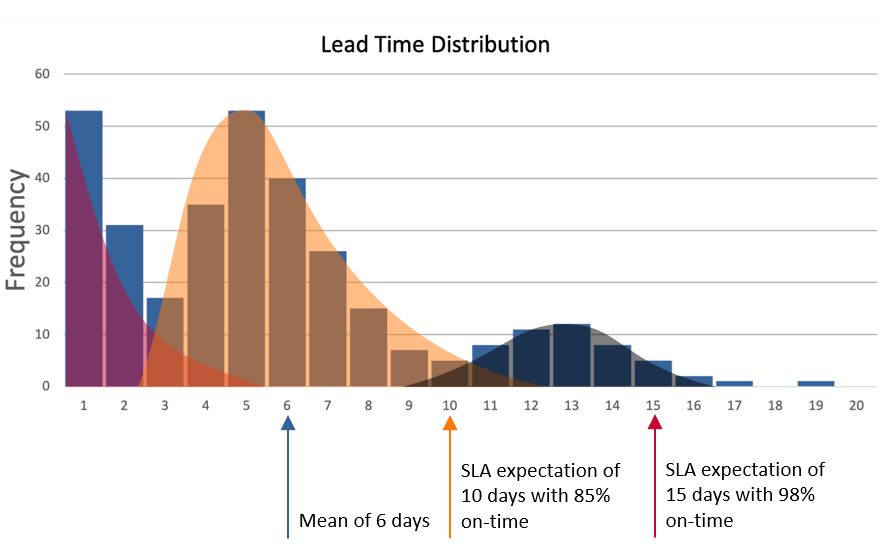

Easy to say: “Don’t estimate.” What should you do instead? With Kanban, you forecast using historically observed lead time. Lead time does not correlate to size, or complexity because flow efficiency is almost certainly very low. The biggest influence on lead time is delay and queuing discipline (or a lack thereof). The size of a piece of work, is not a useful piece of information, even if the size estimate was highly accurate.

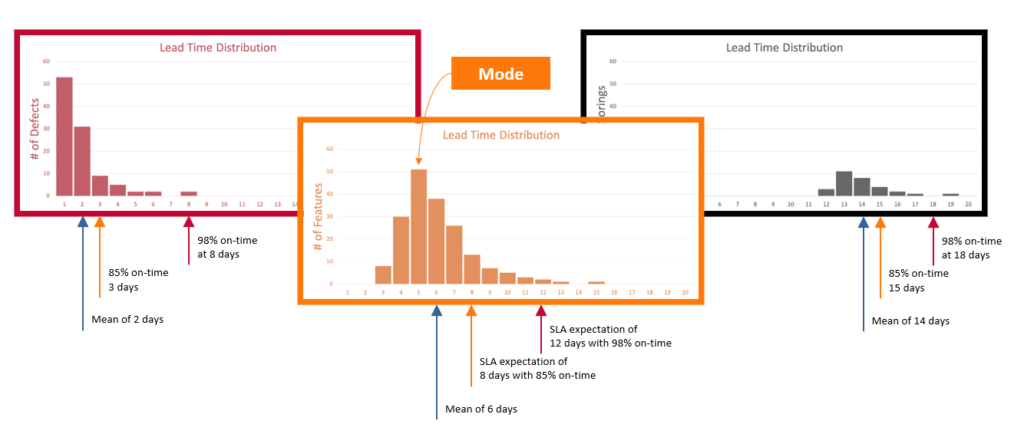

I remember working on building products for the finance department. The first work item type we worked on were “new builds”. When we started to release the increments of our product, we also started to receive feedback which resulted in a new work item type: change requests. Additionally, we didn’t avoid defects and had to solve them immediately, as they affected client-facing product. We realized all that nuances by analyzing the lead time data and listening to clients’ feedback. Noticing multi-modal lead time distribution and analysis of lead time and data points showed us that we don’t have one work item type anymore, but three. We created three lead time distributions from the original one and established SLAs based on them. The “size” of these items was a natural consequence of understanding work item types and clustering the ones which were similar in nature – and hence size.

The below example from the Kanban Systems Improvement class explains how you can identify and read multi-modal data.

Things of dramatically different size will be different work item types. Some guidance might be that if you never see the ticket moved, maybe it is too big. Or perhaps you need a portfolio board or 2-tiered hierarchy, so that you can see the things moving.

When you have identified some consistent type of work, it could be even something huge. Let’s use another example. If you build cruise ships, a ticket for a cruise ship goes on the board. If we are in the cruise shipbuilding business, then the amount of time and energy that takes us to build a cruise ship is something we know and understand. Having one cruise ship, and next cruise ship, and the next cruise ship – we can start building a lead time histogram, as they are all the same type of work. Then one day Richard Branson walks along, and he says: “You know, I’m thinking of buying the cruise ship for my new Virgin Voyages cruise line, and I thought I might place an order with you. If I order it this week when it will be ready?”

If we know, what we are doing, because we are Maturity Level 3 or Maturity Level 4 cruise liner construction company, we can give him an answer. We might be able to say: “We will have that for you by July of 2024, Richard. How about that?” And we know this is the promise we can keep.

It is a significant change between Maturity Level 1 and Maturity Level 2, which is the moment when you start seeing different work item types.

What should you do?

Develop analysis skills, pay attention to your environment and the language people use – they may help you with identifying work item types in your process.

There is more!

Imagine you have a 2% flow efficiency organization. It means that only 2% of the lead time is the actual working time, where things are in the activity column and they are being worked. 98% of the time is a delay. Therefore, the size of the ticket and the actual work is a trivial amount compared to its lead time. Hence, what you try to estimate is not the size of the actual work, but the size of waiting time or waste.

For the same work item type the flow efficiency will produce more variability than a size itself.

So, what should be the “size” of my ticket?

Let’s focus on some pragmatic advice to this question:

- Don’t bother with estimating size. Let a ticket into the system, analyze it as an option in your upstream, use lead time data to decide when to start working on it in downstream.

- Understand your work item types. Listen to what people say, what language they use, when they talk about their processes and work to be done.

- The work item should be “small” enough to allow you to see the progress (or lack of progress – blocker, waiting dependency). If your item stays for few days/weeks in one state, and you lose the track of dependencies, cause it’s all the time “in progress”, then you should look for something more granular.

- Your work item should be “big” enough to not create the overheads. If you spend more time on creating and moving an item through the system than working on it – it means that you need something level higher.

- Use the ticket design to support you in making confident decision. So that when you look at it, you know “what’s going on” and you don’t need to deliberate about it. Of course, this perspective, as everything else, requires some time for trials and probing, and you may need to experiment with different approaches. Be patient. Improve collaboratively, evolve experimentally.

If you want to learn more about real options, option pricing, and cost of quality, we teach this stuff during Kanban for Design and Innovation class. Check out our schedule!